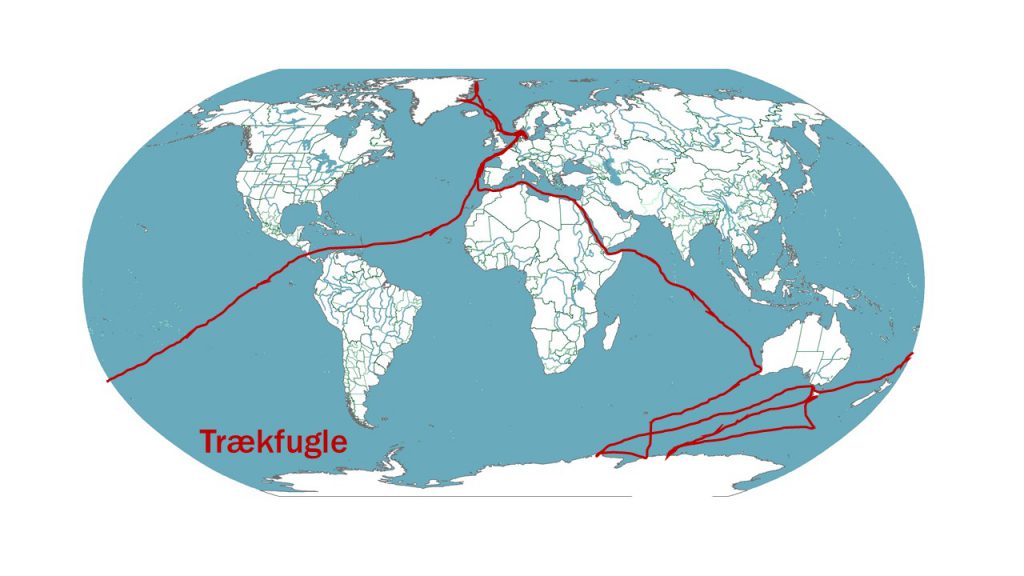

Migratory Seabirds

J. Lauritzen’s polar sisters

Nella Dan was the last of shipping company J. Lauritzen’s ‘migratory birds’, the vessels that shuttled back and forth between the Arctic and the Antarctica, year in, year out. J. L.’s polar ships represent a unique chapter in Danish maritime history that goes far beyond boyish adventures and tall tales.

It is a history of geopolitics, upholding sovereignty, claiming the unknown and securing supply lines all the way to the last outpost.

J.L’s fleet of polar ships served as supply, expedition and research vessels for Denmark, Australia, Germany, the United Kingdom, Belgium, France and other nations from 1952 to 1987.

The polar fleet

In 1931–33, Denmark challenged Norway for sovereignty over Greenland at the International Court of Justice in the Hague, a conflict that later led to the establishment of the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol after the Second World War. In 1959, Australia signed the Antarctic Treaty, which requires the signatories to live up to their obligations and protect their sovereignty.

The ‘migratory birds’ became the link to the civilian world – and their tireless work made it possible to establish the field of modern marine biology and environmental research with marine studies, monitoring marine mammal population sizes, monitoring whaling and many other tasks in the Arctic and Antarctica.

In addition to the most remote Arctic and Antarctic stations, J. L.’s polar fleet also regularly travelled to northern Finland, western Greenland, the North West Passage and St. Lawrence, Canada. In many of these frontier locations, J. L.’s red ships were often be the first to arrive as heralds of spring in the polar regions.

In its heyday, J. L.’s polar fleet included 20 ships, among them the four expedition ships Kista, Magga, Thala and Nella Dan.

Photo by Svend Aage Nielsen

Photo by Svend Aage Nielsen

The beginning

The shipping company J. Lauritzen’s involvement in the polar regions dates back to the time just after the end of the Second World War. The shipping company faced the need to renew their fleet and find new waters to navigate. Shipowner Knud Lauritzen’s visionary and dynamic approach to shipping sets the course and steers the company into the Greenland trade.

Knud Lauritzens professional interest in Greenland begins during a trip to West Greenland in 1948, when he curiously follows the intense media coverage of Greenland at the time.

At the threshold to the 1950s and the start of the Cold War, lead has been discovered in Mestersvig; the Royal Greenland Trade ship G. C. Amdrup is lost at sea; the Daneborg and Danmarkshavn stations are established; and the G50 report heralds a new political agenda for Greenland. Knud Lauritzen seizes the opportunity and enters into an agreement with the Danish state to sail to North-East Greenland, in part as a way of upholding Danish sovereignty and maintaining a secure supply line for the Sirius Dog Sled Patrol.

J.L.’s first actual polar expedition ship was the renowned Kista Dan, which was put into service in 1952. The adventure had begun.

“Kista Dan”

Already the following year, in 1953, similar arrangements were made with, first, Australia and then Britain to assist these nations in delivering equipment, setting up stations and upholding sovereignty over their Antarctic territories. Kista Dan soon had a busy schedule.

Kista Dan’s first expedition for ANARE is depicted in the Australian documentary film ‘Blue Ice’, which documents the development of the Australian stations.

This expedition marked the beginning to a close and long-standing collaboration between shipowner Knud Lauritzen and polar scientist Phil Law (Phillip Garth Law), who as director of ANARE (Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions) was the founder of modern Antarctic research on behalf of Australia.

Phil Law’s wife, Nel Law, is remembered in polar sailing, as Nella Dan was named in her honour.

The Lauritzen Family archive

‘Polar ships have the colour that polar ships are supposed to have’

Kista Dan initially had a grey-painted hull, but soon followed a red-painted mast and crow’s nest, then a red-painted deck, and eventually the entire exterior was painted red.

Making on-board maintenance easier, cutting purchasing costs and achieving a look that stood out were all important points for the shipping company, but the key concern was the positive impact of the red colour on ship security. (Knud Lauritzen in Frivagten, No. 68, p. 18).

In 1955, when Kista Dan came to the aid of the grey-painted sealer Jopeter, which was stuck in the ice pack, the Catalina reconnaissance report said that in clear weather they had spotted Kista Dan at 20 miles’ distance, from an altitude of 5,000 feet, while Jopeter was only discernible against the ice at 4 miles’ distance.

The ships were approximately the same size, and both had their broadside facing the direction of flying. The conclusion was obvious. The red colour was so characteristic and provided such superior visibility against the ice that soon, all J. Lauritzen’s ships were recognizable by their colour.

Photo by Magnus Olafsson

‘The red golden age’

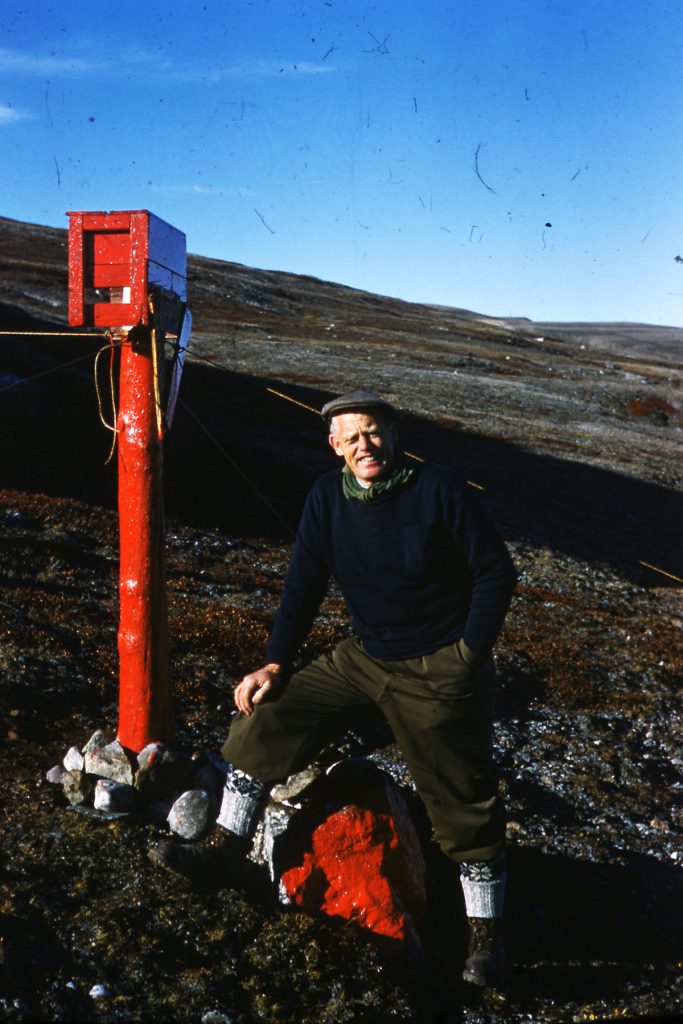

From the pioneering days of the 1950s, the golden age gained added momentum throughout the 1960s, the heyday of the polar fleet. The shipowner himself, Knud Lauritzen, ran the fleet with passion and dedication, and he personally took part in several trips, especially to North-East Greenland.

‘In the years leading up to 1959, a fleet of eight regular, red-painted polar ships for shipping, expedition or research purposes was systematically developed. At the same time, some of the ordinary freighters were heavily reinforced to deal with ice in order to prepare them for Greenland and Canada, in the latter country especially on the St. Lawrence. This systematic development of a polar fleet continued into the 1960s, although the mine in Mestersvig seemed to be depleted in 1962. The highly visible – originally an impractical white – and recognizable red polar ships earned more mere publicity and prestige than profits, however, considering the risks and effort. They were never a huge boost for the bottom line – rather a particularly demanding sport or playground, with Knud Lauritzen as the active participant. Risky and expensive, sure, but also much more meaningful and fun than going to a casino in Monte Carlo. He later described how the Danish shipping tycoon A. P. Møller once quipped that J. Lauritzen was the only shipping firm that would take on such a high-stakes adventure. J. Lauritzen was fully privately held and thus did not have a board or a group of shareholders demanding cost-benefit estimates etc.’

(Ole Lange: Logbog for Lauritzen 1884 – 1995 [Logbook for Lauritzen 1884–1995], p. 208)

Former ship’s mate Bjarne Rasmussen comments in his book Dansk Polarfart 1915-2015 [Danish polar sailing 1915–2015] that the Danish polar ships achieved a high rate per day when they were chartered out to, for example, the Royal Greenland Trade or ANARE. The high rates reflected the high risk of major and costly damage to the ship’s hull when sailing in icy conditions in polar waters, regardless of the season. One year’s good earnings might easily be swallowed up by a tough season in the icy waters.

Lauritzen’s red polar sisters may have been built with an icebreaker stern and reinforcements to withstand the ice, but they were not actual ice-breakers with impressive engine power. They were constructed to travel alone, squirm their way out of trouble and withstand the pressure of the ice. They were ships that could pop out of the ice like a cork once the ice pack began to close in.

Ships occasionaly met in these waters. In in 1964, former steward on both Magga Dan and Nella Dan, Hans O. K. Lassen, captured an incident where the new-built Nella Dan helps her slightly older sister Magga Dan (named after Crown Princess Margrethe) make it through the ice to Scoresbysund.

With indomitable reliability, the red ships shuttled back and forth, with the regularity of migratory birds, between the Arctic and the Antarctic, year in, year out. The ships and their crews have left their mark. At least 24 locations in the Australian part of Antarctica are named after related events and personalities and the red ships themselves. Places such as Dahl Reef, Petersen Bank, Wollesen Islands and Nella Rock bear testimony to events and discoveries in connection with Antarctic mapping, expeditions and exploration.

From the late 1960s, the polar fleet is modernized. First, Kista Dan is replaced, in 1967; then follows the sale of Magga Dan in 1969; and from 1971 Thala Dan and Nella Dan are the only remaining red migratory birds. While the J. L. shipping company undergoes major changes in the 1970s, Thala and Nella continue on their migratory paths for another decade, a time of profound global changes affecting both the world markets and the internal workings of every ship.

The turbulent period of upheaval and transformation from the late 1960s through the 1970s also affects life on board the polar ships. A new generation is about to take the helm. The on-board team spirit of the 1960s, when the entire family sailed along, changes to a new sense of team spirit among young crews that stand up to the changing times. Towards the end of the decade, in 1978, Knud Lauritzen passes away, and with his passing, the polar adventure begins to draw to an end.

In the early years of the next decade, Thala Dan is sold in 1982, leaving Nella Dan as the last of the migratory birds in the fleet. Throughout the 1980s, Nella Dan presses on with stubborn persistence, defying the odds, ploughing Antarctic waters for yet another 5–6 weary and dramatic years.

Her track record of more than 40 voyages to North-East Greenland and 85 voyages in Antarctic waters corresponds to numerous circumnavigations of the globe. With more than half a million nautical miles in the Antarctic, Nella Dan holds the record of any ship in Australian service.

Thanks to all the friends of Nella Dan

The saga of J. Lauritzen’s polar ventures is extensive, and the present account is far from exhaustive. Stories and documentation lie scattered among sources and archives that we hope to help bring together and make accessible through the association’s activities and communication on this website. In our work, we draw on several key sources, magazines and publications that have dealt with Nella Dan over the years.

The most central sources for knowledge about J. Lauritzens polar engagement are the shipping firm’s magazines ‘Frivagten’ and ‘Lauritzen News’ as well as the two books ‘Eventyret i Antarktis’ (The Antarctic Adventure) by Povl K. Hansen, Vilhelm Pedersen, Georg Røn et al. (2010) and ‘Dansk Polarfart 1915-2015’ (Danish polar sailing 1915–2015) by Bjarne Rasmussen (2016).

We owe special thanks to:

- The Lauritzen family for access to their private film and image archives

- Lauritzen Veteranerne (the Lauritzen Veterans) for their friendship and access to accounts about the red migratory birds

- ANARE Club in Hobart and Melbourne for access to documentation of Nella Dan’s track record and sources of stories

- The private archives of Bjarne Rasmussen and Povl Kjeld Hansen and their life-long dedication to the history of Danish polar sailing

- The archives on J. L.’s polar activities at Springeren in Aalborg and M/S Maritime Museum of Denmark in Elsinore

- All the friends of Nella Dan who have generously wanted to share their adventures

Photo by Martin Betts