At sea ...

‘Rollin’, rollin’, rollin’ …’

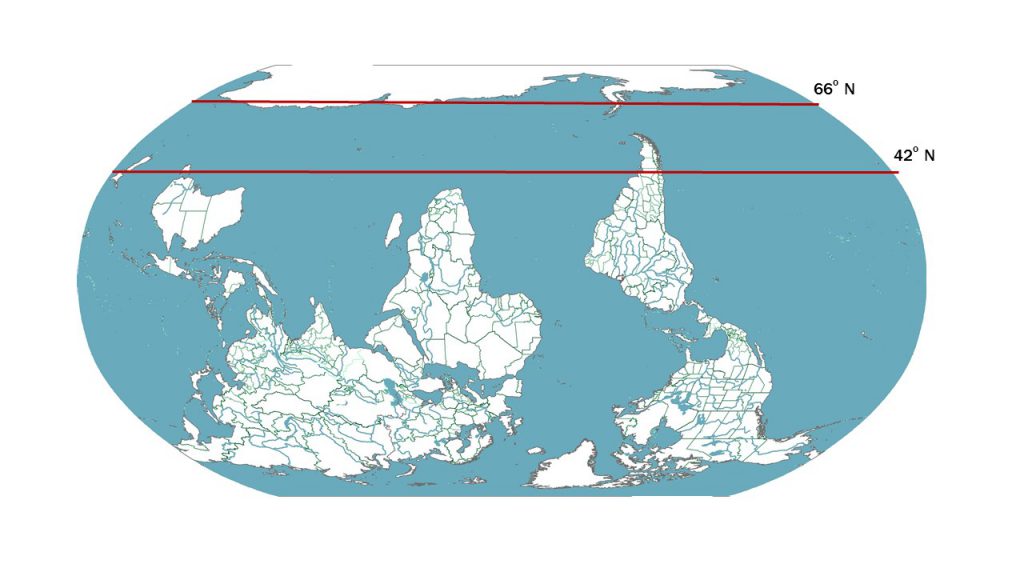

The ocean south of Australia is truly vast. Unfathomable for a Caucasian landlubber. From the initial departure from River Derwent in Hobart, Tasmania, at approximately 42 degrees south to arrival in the Antarctic at around 66 degrees south, there is nothing but water all the way. Only the very tip of South America dips its horn into this gigantic body of water.

In the northern hemisphere, this corresponds to running an egg-slicer in a straight line just north of Rome, Beijing and New York and then filling the tub with water almost all the way to Murmansk along a line running north of Fairbanks, Reykjavik and Trondheim.

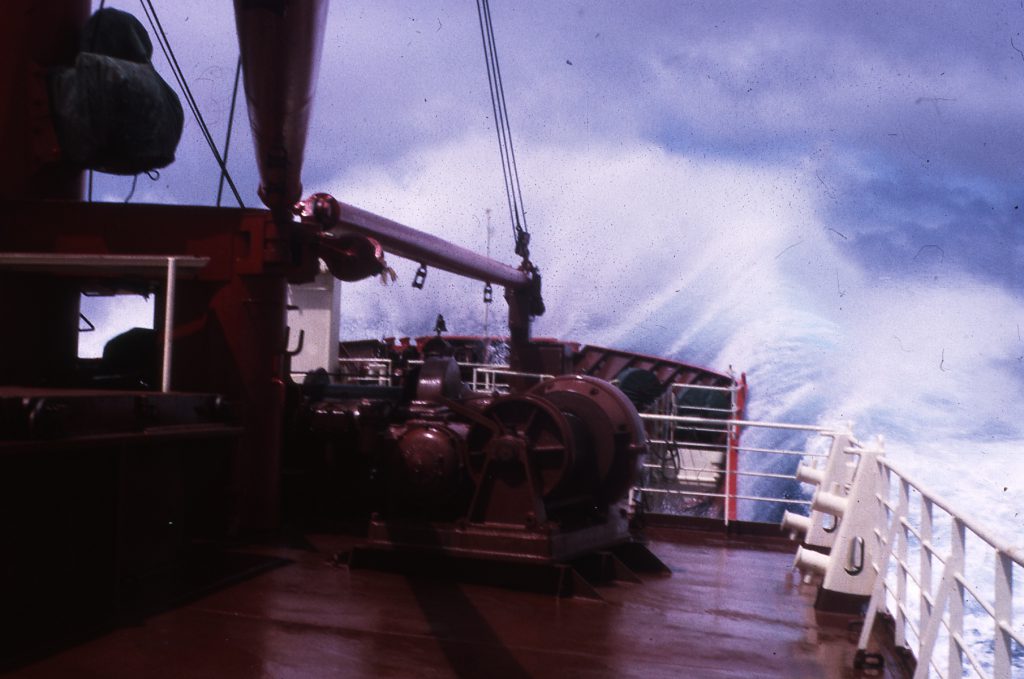

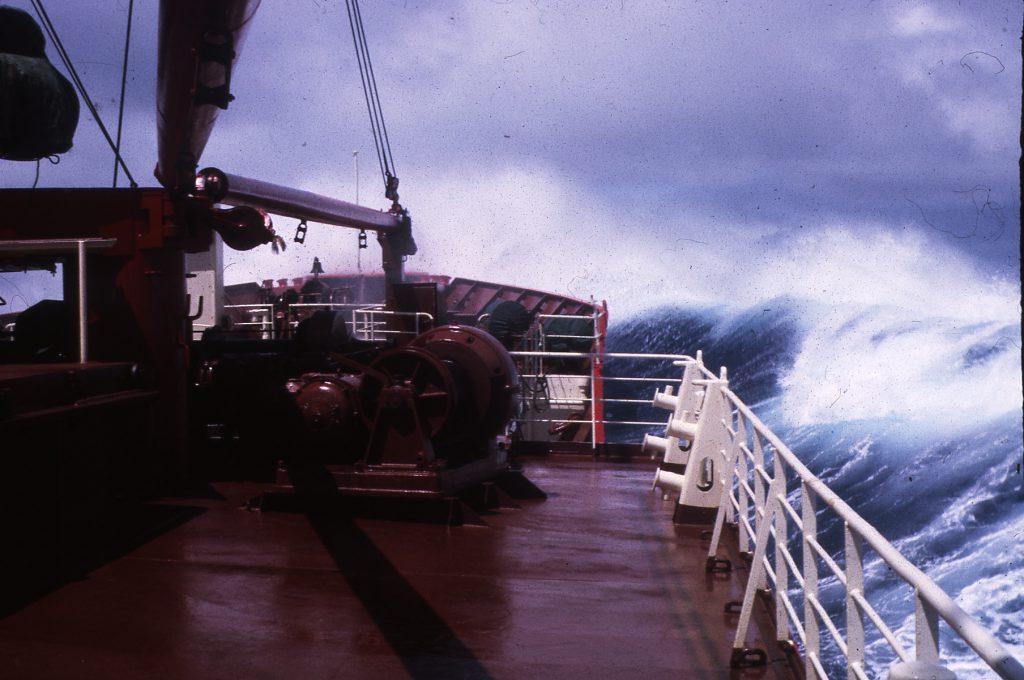

That makes a sea voyage from Australia to the Antarctic on a ship such as Nella Dan difficult to capture in words. There is an unbelievable amount of water to deal with. For a little red ship with a maximum speed of 12.5 knots built for icy conditions with a round hull and no bilge keel, 15-metre waves make for a combined rollercoaster ride and funny house, around the clock, for days on end.

As Kim Stanley Robinson aptly wrote in his book Antarctica,

‘Below the 40th latitude there is no law; below the 50th no god; below the 60th no common sense and below the 70th no intelligence whatsoever.’

The Southern Ocean is notorious for its powerful westerly winds and heavy seas that travel around the globe without being blocked or diverted by land. During every single season in Nella Dan’s 27-year history, the roaring forties and the furious fifties took the little red ship on a wild ride. Like other polar ships at the time, Nella Dan was constructed without a bilge keel and stabilizer fins, so the ship was often put through the wringer, before she reached shelter by the ice below the 60th latitude.

That the loss of cargo and the damage to the ship or crew was not worse than it was, can be attributed to the crew’s seamanship and their ability to make the most of Nella’s strengths, keeping the ship always in shipshape condition, and making sure that all the lashings of cargo and gear had been checked and double-checked … and then checked once more for good measure.

“But she’s good in the ice…”

Stories from crew members and, perhaps especially, the guests travelling on Nella Dan are testimony that a trip through the spin cycle in the southern waters was an experience that called for a strong constitution, a good sense of balance and sturdy inner organs. A sense of awe was evident in the eyes of the passengers lined up by the gangway at the start of a new season. Station staff, scientific teams and technicians were sent along with the comforting assurance that ‘If you survive the next two to three weeks’ voyage to the ice, you’ll surely survive the next ten months on the icecap in the dark until she returns to take you home …’

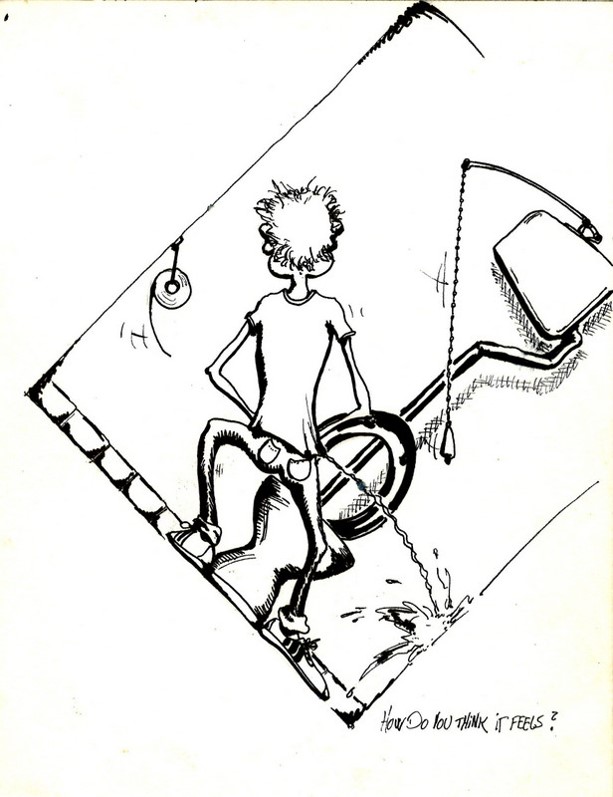

There is many a tale of rough weather lasting for days, with Nella Dan constantly rolling 35–45 degrees, and everyone on board acquiring the skill of sleeping while alternately standing upright and upside down in the transverse bunks. Even for seasoned seafarers, a week of rough weather can severely challenge the laws of physics as well as the traveller’s body chemistry and mental resilience. For newcomers, there was scant relief. There are even stories of passengers who spent two to three weeks being seasick, to the extent that both their mental and physical health was at risk.

One of the best cures for seasickness, of course, has always been to stretch out under an apple tree in a peaceful orchard and gaze out over the meadows … A shame, only, that the cure is so far away. There was limited consolation to be found in the knowledge that things would settle down once Nella reached the ice. As ship’s mate Arne Detlevs would often say reassuringly, when the going was really rough: ‘But she’s good in the ice …’

‘A sorry traveller’s tale’

Although we had left Melbourne in moderate weather, the morning brought a complete change, we had travelled through a ‘bad’ section of water and the ship would not stop its rock’n and roll’n. My body was paying me back for all the punishment I had given it on the previous day. I was accommodated in cabin number four, on the port side, and on wakening I headed straight for the toilet opposite, where I made myself as comfortable as one could under the circumstances. Space was at a premium on the Nella and the toilets were not an exemption to the rule, there was barely enough room to kneel on the floor and hang one’s head over the cold stainless steel bowl. I had never before experienced a hangover of such magnitude, but when coupled together with the most agonising experience of seasickness, I would not have dismissed the thought of dying as a cause of it.

Much to the annoyance of other desperates I remained there for the next one and a half hours during which time the silence of my day was broken by the hooting of horns and alarms; my agony was so intense that I remember thinking to myself that if the ship was sinking, this would ease my pain and solve everything. I ignored the sound of the alarms and the knocks on the door until the snib on the door was unlocked from the outside by one of the Danish crew. He muttered in very broken English that the alarms were for a ‘Fire and Lifeboat Drill’ and that all passengers should be up on deck, and besides, you can throw ‘IT’ further from the top deck! My thoughts were different to his, but he was more persuasive and besides, he would not go away.

During the next ten days I only ventured out of my cabin to attend to the weather obs that I was required to perform, and for my frequent trips to the small room opposite. I heaved until there was nothing left to heave and then heaved some more. In that time, I was to learn of the ferocity of the ‘Roarin’ Forties’ and the ‘Furious Fifties’ and the effect that these notorious waters can have on the VERY small, round-bottomed hull of the Nella. She bobbed around like a cork, and my stomach bounced around with every wave that crashed against this little ship. I didn’t realise that a ship of this size could endure such savage seas for so long without suffering some structural damage, nor did I quite understand how a human body could endure such pain and agony for so long without breaking.

I had not really eaten for the duration of the voyage, except for the occasional piece of dry toast, which didn’t stay down for too long. I was a physical mess and my mental state wasn’t much better. I had made many visits to Doc Birss for those ineffective seasickness pills but I was too far gone for any help, they just rattled around in that empty pit of a stomach.

(Excerpt from Neil Brandies’s story of the trip down to Mawson in December 1978, first published in Aurora, ANARE Club Journal, Vol. 7, No. 3, 1988, pp. 28–29)

One hand for the ship, one hand for yourself …

At sea, workplace safety rule no. 1 has always been to remain alert and to keep one hand free for your own safety. On board Nella Dan, safety was even more crucial than on many other ships. Safety rules were strictly enforced, and all possible measures were taken to keep everyone safe. Everyone quickly learned to ‘make ready for sea’.

The transverse bunks were also one of Nella’s safety measures, as they kept people from being thrown out of the bunks when she rolled. As a downside, people had to learn to find rest while alternately standing upright and upside down.

Everyday chores could be a challenge at times, when it was hard to tell the bulkhead from the floor. People were quick to learn never to fill cups, pots or buckets more than half, lest the liquid spill out when the ship took a 45-degree roll.

One of the regular daily tasks involved checking that cargo and gear had not shifted, carefully inspecting all chains and lashings. This was no easy task, as it involved climbing on and among containers, boxes and miscellaneous cargo in the hold to check the chains and lashings, while the ship might be heaving to in a hurricane, pitching violently up and down. Many a good seaman has come back from the morning watch with bruises from being knocked about in the hold and handling unwieldy gear.

And pity the mess man or deck boy who did not master the use of the fiddle rails in the mess room and salon. The place could get very messy indeed when the soup went flying across the room.

Throughout the years, fortunately, severe personal injuries were rare. Some serious accidents did cast a dark shadow on Nella Dan, as when cook’s mate Kim Nielsen fell down the ladder from the galley to the cold store and larder in 1985 in rough weather.

Kim died from the head injury he incurred in the fall. A dark day for everyone on board and for his family.

R.I.P